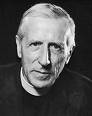

It is infinitely more worth while to present, for the time being, a mixture of truth and error, than to mutilate reality by trying prematurely to separate the wheat from the tares. I have followed this Gospel principle without hesitation, since it is the principle of all research and scientific progress.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, letter 1917.

I just discovered this today, and to me it articulates the right approach to enquiry of any kind. When people violate it - either by self-censoring and refusing to speak while they are uncertain, or by pretending that they understand something they don't - they distort not only their own minds, but those of others.

11 comments:

It's a highly transmittable state known as falsuvidentecommunophobia -- fear of being seen to be wrong in public. It is endemic in schools of philosophy, and afflicts men more frequently than women.

Prolonged immersion in alcohol is said to be an effective cure in some cases.

The desire to be seen to be 'right' is extraordinarily powerful. We see it here, we see it there, occasionally we even see it in ourselves. Knowledge gives power and prestige and status, and these goods are valued.

There's a fair amount of swatting on this blog - and it's all to do with being seen to be right. Perhaps that's not entirely just - there's also a strong impulse towards freedom, and the proper use of talents to discover this.

But it's becoming clearer to me that we forget love at our peril. It's not personal; I would just like to remind us not to forget it.

If there's a job of work to be done to clear out the undergrowth and open up broad vistas and avenues - then so be it. We can all put our shoulder to that in our various ways.

But if we have felt - as has been expressed here often - that self-censorship is the curse of all enquiry, then we have to make it easy and worthwhile for people to be wrong.

Otherwise, not many will step outside the door of their comfortable resting place.

Encouraging 'easy to be wrong' (hollow laugh)- that's easy enough! But how many will venture forth if to do so is to invite slings and barbs? Even silently unspoken?

That's where love comes in.

Anonymous is quite right about women in this respect. Possibly because we're used to being wrong. And know it for the sham that it is.

I think you've hit on something very deep in the psyche of some of us, Kevin.

It's not something that LM would have welcomed -- it's as if, since those early test-it-yourself days, we've been so flooded with 'spiritual information' that it's begun to count for more, as a mark of a 'good student' than personal experience; which is sometimes looked on with suspicion by those who cling to the word rather than the spirit.

A sort of intellectuals' version of devotion...

Even the other day I saw that fear of 'not getting the theory straight' in the eyes of a senior student. It was dreadful to see. As if they feared they'd backed the wrong horse, I thought to myself.

That must go deep. Not thinking for oneself and not wanting to, wanting to be told 'the truth' is what leads to cults and their disasters. We should be clear of that by now ?

Not sure it's a question of 'should' or, rather, it is a question of 'should' because 'should' locks - rather than releases.

So it's a matter of release. We've no doubt all had that experience of setting forth on an exposition and getting halfway along the plank when.... help....it's all gone wobbly and we know it doesn't add up. Backing the wrong horse is a good metaphor, a similar sinking of the stomach.

This is the emotional ground that needs releasing. And this must surely be where the work now begins. I'm much more interested in this - as the next stage for the School - than almost anything else.

To put it in context, I don't know about you but I rarely learn anything from being 'right' but much from being 'wrong', so it has to be alright to be wrong. That's spaciousness, that's a diminution of fear, that's a willingness to explore the possibilities - indeed, much of what we have spoken of here.

If this is so - if it's the desire to be right that binds us, as I think it does, then how to unwrap those bindings? We don't really want them.

There is a fear of being wrong or of not knowing, but it's one philosophers just have to overcome. It's not as if by making a few things up, or of suppressing just a few awkwardly real questions, we can make progress. This is a case where a tiny amount of poison in the dal makes all the dal poisonous.

When I was unceremoniously thrust into tutoring, I took a decision which was that I would say nothing which I did not believe in and understand. That decision has served me very well.

Maybe it comes back in a way to what Son of Moses was saying about 'lowest common denominator'; personally I would rather have a very low form of knowledge, and know it and believe it thoroughly, than pretend to the highest knowledge in the world. Not because one prefers the former, but because you cannot build the temple on shaky or absent foundations.

I believe that some people along the way (because of fear or ambition) have not followed the principle expressed by Teilhard, and they stepped off the path. That is unfortunate for them and for us as well, so long as we don't realise what we need to do to get back on.

What Laura says earlier about love is essential. More Teilhard:

It is not tete-a-tete or corps-a-corps that we need; it is heart-to-heart.

What you say, Kevin, is a very good principle for a tutor - for anyone for that matter - but I wonder if we could take it a bit further?

What you have stated serves well. Rather like a mountaineer who tests the cleats (or whatever mountaineers use) before ensuring that his next step is grounded in solid rock, he ensures that no mistakes are made so far as is possible.

But there's a further step which is to establish a forum where the outcome is not known, where people can be encouraged to step out of an habitual method, where 'right' and 'wrong' responses become irrelevant.

Why would one want to do this?

Only because to do so is to admit the unknown. And there's freedom there. And grace.

I'm not sure I know what you mean by a forum where we 'admit the unknown'.

I've suggested recently that there should be a 'meeting in a circle' format in situations where the tutor is neither much wiser nor more well informed than the students. Maybe that expresses it sufficiently? Or not? What do you think?

I'm feeling my way here because, by definition, there is no definition of the 'unknown'.

In my previous post I speak about letting concepts of 'right' and 'wrong' go. That could be extended to as many mental constructs as bind the individual. There has to be a willingness to step out of safety.

That was the foundation of my earlier post, Dare to Peace. Suppose that peace is not safety - at all? What happpens then?

Think, for a moment, of the times when you've been happiest - or most exalted - in the School. Think of the times when you've been most bored or weary.

What's the difference? Could it be that one admits the unknown - which is then recognised and known.

And the other just treads a well-worn path

I was talking to a friend this morning who said that, in his group, the men are very competitive. Those who were more learned in the teaching tended to take the lead while the others kept quiet.

In his view men are always like this. I can't disagree. Call it 'ahankara by gender'?

How much of an impediment is this? I can see that, in the race to get the biggest cuts of meat, our male forbears needed to be competitive to survive.

But engaged in spiritual work?

This links with Kevin's observations on status and elites in another post. Not just an annoying trait but positively injurious it may seem.

I think that in the School there is an obsession with gender difference that goes way too far (I'm not saying you're guilty of this here, by the way!) Women are supposed to be manipulative and men are supposed to be childish. If there is a case of sexual misdemeanour the reflex response is therefore to blame the woman, because obviously the man is putty in her hands and could not resist. This can apply even if we are talking of a man in his forties and young, emotionally unstable female student.

I've also experienced the effect of this mantra being hammered into impressionable young people.

So I think that although there isn't much we can do about people's inbuilt gender difference, we should at least not magnify it by stereotyping.

Here's an Advaita principle: we are all from one stock. That common heritage far outweighs out any amount of gender /race / class / educational difference.

The advaita principle has to be helpful in thinking about gender differences - as it does with all areas of life.

Gender is an important element of School life, not least because a great deal is made of it. It always seems to come back to Adam, Eve, the apple and the serpent. This, despite the School's cosmology otherwise not being based on the old Testament.

There's plenty of potential for injustice in such an approach.

Post a Comment